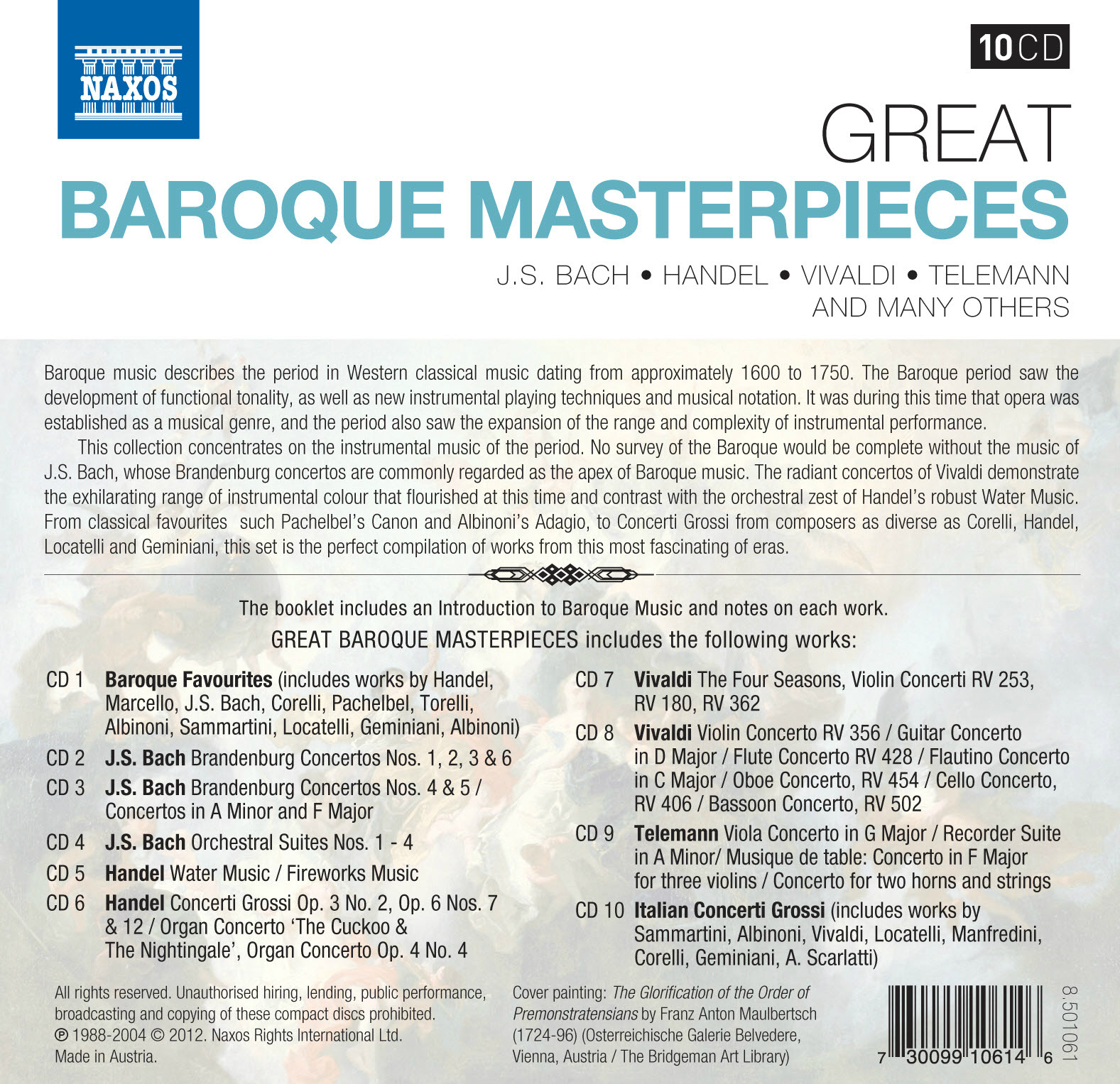

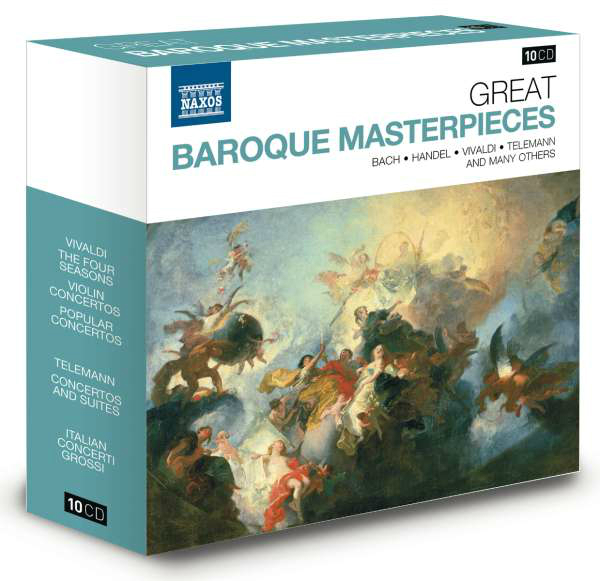

GREAT BAROQUE MASTERPIECES Introduction Various definitions have been proposed for the word baroque, since its first application to music in the eighteenth century. Derived from the Portuguese barroco, a pearl of curiously irregular shape, leading to the French baroque, it was adopted, sometimes pejoratively, as a term descriptive of certain styles in art and architecture, suggesting the exuberance of Bernini and the decorative architectural fashions that followed the Gothic. Whatever its original use, the word, in music, is now generally accepted as the designation of a period from c. 1600 to c. 1750, a period that can conveniently be divided into three of fifty years, Early, Middle and Late. Periodisation, of course, has its dangers and must be used with some discretion. Nevertheless the Early Baroque period, from c. 1600 to c. 1650, covers the age of Claudio Monteverdi and the development in Italy of the art of opera and concurrently of styles of harmony and vocal writing that brought a new strangeness of proportion. The Middle Baroque period, from c. 1650 to c. 1700, is, in England, the age of Henry Purcell, and in Italy the age of the widely influential Arcangelo Corelli, whose instrumental style and forms provided a model for the following generation. The Late or High Baroque, from c. 1700 to c. 1750, is now the most familiar of all. This is the period of Antonio Vivaldi in Venice, of Johann Sebastian Bach in Cöthen and then Leipzig, and of the Italianate German composer George Frideric Handel in London for the greater part of his life. The Late Baroque brought to a height the art of tonal counterpoint, the construction of fugal textures, instrumental or vocal, in which a melody is first proposed by one voice, answered by others in turn, one melodic line set against another. In instrumental music it brings the church sonata and chamber sonata, the first finding room for contrapuntal textures and the second for sets of dance movements, often scored for two melody instruments, with a bass instrument and a chordal instrument, harpsichord, organ or lute, to supply fuller harmonies. Parallel to these trio sonatas of either species is the orchestral concerto, whether in the form of a concerto grosso, in which a smaller group of instruments is contrasted with the full orchestra, or as a solo concerto, a form perfected by Vivaldi. During the baroque period the orchestra developed from a varied collection of instruments to something approaching the form it has today in the string section of a modern orchestra. By the early eighteenth century the orchestra often consisted of first and second violins, violas, cello and bass, with a chordal instrument. This was the form of the orchestra generally used by the violinist Vivaldi. The instrumentation, however, could be varied, as in Johann Sebastian Bach’s vividly orchestrated Brandenburg Concertos, or, to a lesser extent, in George Frideric Handel’s concertos. The solo concerto of the High Baroque brought not only the varied use of solo instruments found among the five hundred or more concertos by Vivaldi, but the appearance of the keyboard concerto, whether in Handel’s Organ Concertos, designed to entertain an audience in the intervals of an oratorio, or in the Harpsichord Concertos Bach wrote or arranged for himself and his sons with his Leipzig University Collegium Musicum. The present collection concentrates on the instrumental music of the period, principally of the High Baroque. The years also brought new forms of opera, from the mixed genres of the Middle Baroque and the old age of Monteverdi to the formal opera seria adopted by Handel and his contemporaries. In England it brought a new form, the English oratorio, largely Handel’s creation, while France had seen the apotheosis of French ballet and opera first with Lully and then with Rameau. CD 1 starts with an instrumental excerpt from a Handel oratorio, The Arrival of the Queen of Sheba from Handel’s Solomon. The last CD ends with a concerto grosso, by Alessandro Scarlatti, whose operatic overtures led the way to the new symphonies of future generations. Every age, we are reminded, is an age of transition. Keith Anderson

CD 1 Baroque Favourites The first half of the eighteenth century saw a musical synthesis of styles from Italy, France and Germany. From Italy came ‘song’, from France ‘dance’ and from Germany a more academic approach that could weld these song and dance elements into a whole. This collection provides examples of favourite Baroque works, incorporating these three different styles. The Italian composer Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713) spent his later life in Rome, where he established himself as a violinist and composer. Contemporaries and later composers were strongly influenced, in particular, by his Concerti grossi, orchestral compositions in which a small group of solo players (two violins and continuo in Corelli’s work) are contrasted with the full string orchestra. His so-called Christmas Concerto, designed for performance on Christmas Eve, includes a pastoral movement suggesting the shepherds at Bethlehem in a musical form that was much imitated [4]. Georg Frideric Handel (1685–1759) had met Corelli in Rome during the earlier years of the eighteenth century. Born in Halle, he had worked first at the opera in Hamburg, before travelling to Italy. Recruited as director of music to the court at Hanover, he soon found a way to move to London, where he was at first primarily occupied in the provision of Italian opera. Handel’s melodic facility and the form his musical language took suggest a different balance in the developing baroque synthesis. Nevertheless Corelli, leading an orchestra for Handel in Italy, claimed he could not grasp the latter’s ‘French’ style. While continuing an intermittent connection with Italian opera, by 1740 Handel had found a new musical compromise in a new form, that of English oratorio. The present collection is introduced by the familiar Arrival of the Queen of Sheba [1], an instrumental movement from the oratorio Solomon, first heard at Covent Garden in 1749. Equally familiar is the Largo from Handel’s 1738 opera Serse, originally an aria in which Xerxes is overheard expressing his admiration for the plant life around him [12]. Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) was the son of a musician and member of a musical family of long traditions. on the death of his parents he moved to Ohrdruf, where he was taught by his elder brother and made his early career as an organist with an appointment in 1707 as court organist at Weimar. In 1717 he moved to Cöthen as director of court music for the young Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen, a happy period of his life that came to an end with the Prince’s marriage to a woman that Bach later described as “amusica”. It was at Cöthen that Bach wrote much of his instrumental music, including his violin concertos and his concerto for violin and oboe. only three of the violin concertos survive in their original form including the fine Concerto for two violins. The slow movement is one of particular beauty, the two solo violins in dialogue above the gently lilting rhythm of the bass-line in the orchestra [13]. In Leipzig Bach arranged a number of his earlier concertos as concertos for solo harpsichord or harpsichords. His Harpsichord Concerto in F minor derived its outer movements from an oboe concerto that is now lost and its slow movement, here included, from a church cantata. Accompanied by plucked strings, the solo harpsichord offers a fine melody, gently elaborated [6]. Other concertos, including the work for violin and oboe, have been arranged back from Bach’s Leipzig arrangements of these works for one or more harpsichords and orchestra. The three movements of the Concerto in C minor, BWV 1060 [3] two faster movements framing a central moving Adagio, allow intricate interplay between the two solo instruments. Bach’s Easter Oratorio was originally a cantata, written for performance in Leipzig on 1 April 1725. In the early years of his employment as Thomascantor, Bach wrote a very large number of cantatas, vocal and instrumental compositions for each Sunday and each important festival in the church year. The Easter Oratorio from which the present instrumental Adagio is drawn [10], was revised between 1732 and 1735 as an oratorio to mark the feast. Bach owed much to Vivaldi and other composers in Venice, where the solo concerto had developed. He made his own solo harpsichord arrangement of the Oboe Concerto by Alessandro Marcello (1684–1750), a Venetian nobleman and dilettante. The slow movement of the Oboe Concerto in D minor [2] is here included. Johann Pachelbel (1653–1706) was a prolific composer who had drawn much from his experience of Italian music. Pachelbel served as an organist in Erfurt, where he had connections with the Bach family and taught Johann Sebastian Bach’s elder brother, Johann Christoph, with whom the former lived after the early death of his parents. Pachelbel was able to spend his final years as organist at St Sebald’s in his native Nuremberg. While his other work may be known principally to organists, his Canon and Gigue [5], an ingenious composition originally for three violins and continuo, has enjoyed very wide popularity, appearing in a variety of arrangements. Giuseppe Torelli (1659–1709) was active in the orchestra of the huge Basilica di San Petronio in Bologna, first from 1686 to 1695 as a violist and then, from 1701 to 1709, as a violinist. His main historical contribution was to the development of both the violin concerto and the concerto grosso, but he was also the most prolific Italian composer for the trumpet, with some three dozen pieces, variously entitled sonata, sinfonia, or concerto, for one, two, or four trumpets. The so-called Concerto No 2 by Torelli [7] appeared in about 1715 as the sixth in a series of concertos by Bitti, Vivaldi, and Torelli published in Amsterdam by Etienne Roger, who was also Corelli’s publisher. The concerto is notable for the highly expressive and virtuosic writing for the strings in the middle movement in which the trumpet is silent, but with its marked themes and motoric rhythms it has become a staple of today’s Baroque trumpet repertoire. Tomaso Albinoni (1671–1751) made his prolific career as a composer in Venice. His compositions include a number of fine oboe concertos, from one of which an Adagio is included [8]. His name is best known, however, for an Adagio attributed to him by its true composer Remo Giazotto, who offered it as an elaboration of a fragment by Albinoni [15]. Giuseppe Sammartini (1695–1750), brother of the better known Giovanni Battista Sammartini, was one of the eight sons of a French oboist and his Italian wife and was born in Milan in 1695. With his brothers he performed as an oboist and after 1728 made his home in England, where he was well known as a performer and as a composer, serving as music master to the Princess of Wales and her children from 1736. He had a strong influence on English oboe-playing and his compositions, published posthumously, were held in great esteem for a considerable time. The slow movement of his F major Recorder Concerto, in the key of A minor, is a gently pastoral Siciliano [9]. A native of Bergamo, Pietro Locatelli (1695–1764) was born in 1695 and started his career there as a violinist at the church of S Maria Maggiore, a position he left in 1711 in order to study in Rome. There it is suggested that he took lessons from Corelli, a leading figure in the music of the city. The forms used by Locatelli largely echo those in the published work of Corelli, with the eighth of the Concerti grossi Op 1 set also a Christmas concerto, ending with a pastoral movement, a Siciliano [11], suggesting the shepherds at Bethlehem, a convention widely followed. The violinist and composer Francesco Geminiani (1687–1762) was one of those Italian musicians who found a ready livelihood in England in the first half of the eighteenth century. Born in Lucca in 1687, he was a pupil of Arcangelo Corelli and of Alessandro Scarlatti in Rome. The form of the concerto grosso owes much to Corelli. The third of Geminiani’s Opus 3 set of Concerti Grossi, the Concerto grosso in E minor, has the briefest of Adagio introductions, six bars that lead to a contrapuntal Allegro. The second movement is an Adagio, with a moving quaver pattern sustained at first by the two violins of the concertino. There are contrapuntal entries in the final Allegro [14], the subject suggested by the first violin, repeated by the second and briefly, in inverted form, by the viola and then by the cello.

|