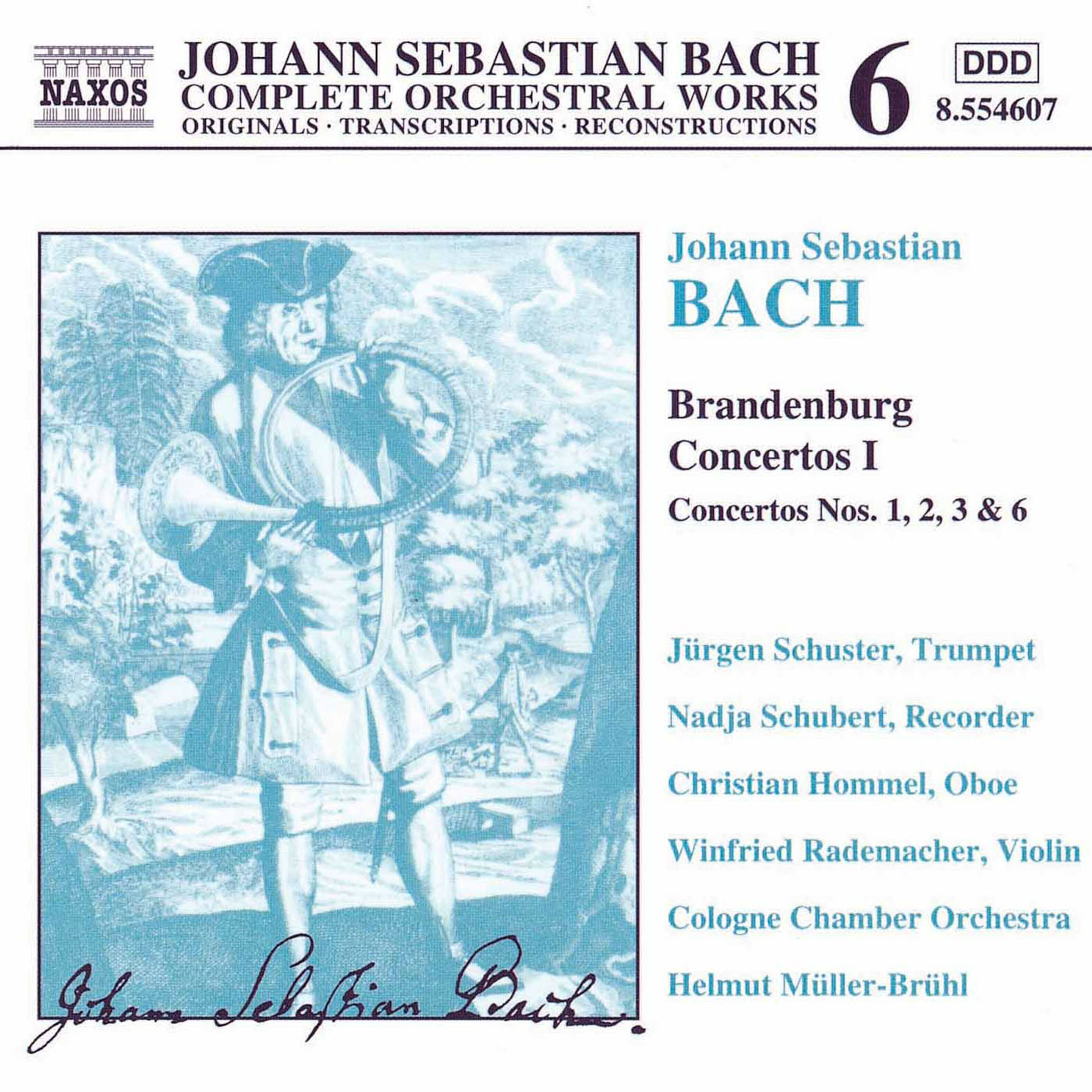

Album Title: Great Baroque Masterpieces (Bach - Brandenburg Concertos 1, 2, 3 & 6) CD 2

Composer Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 - 1750) Track List 1-4. 브란덴부르크 협주곡 제1번 바장조, BWV 1046

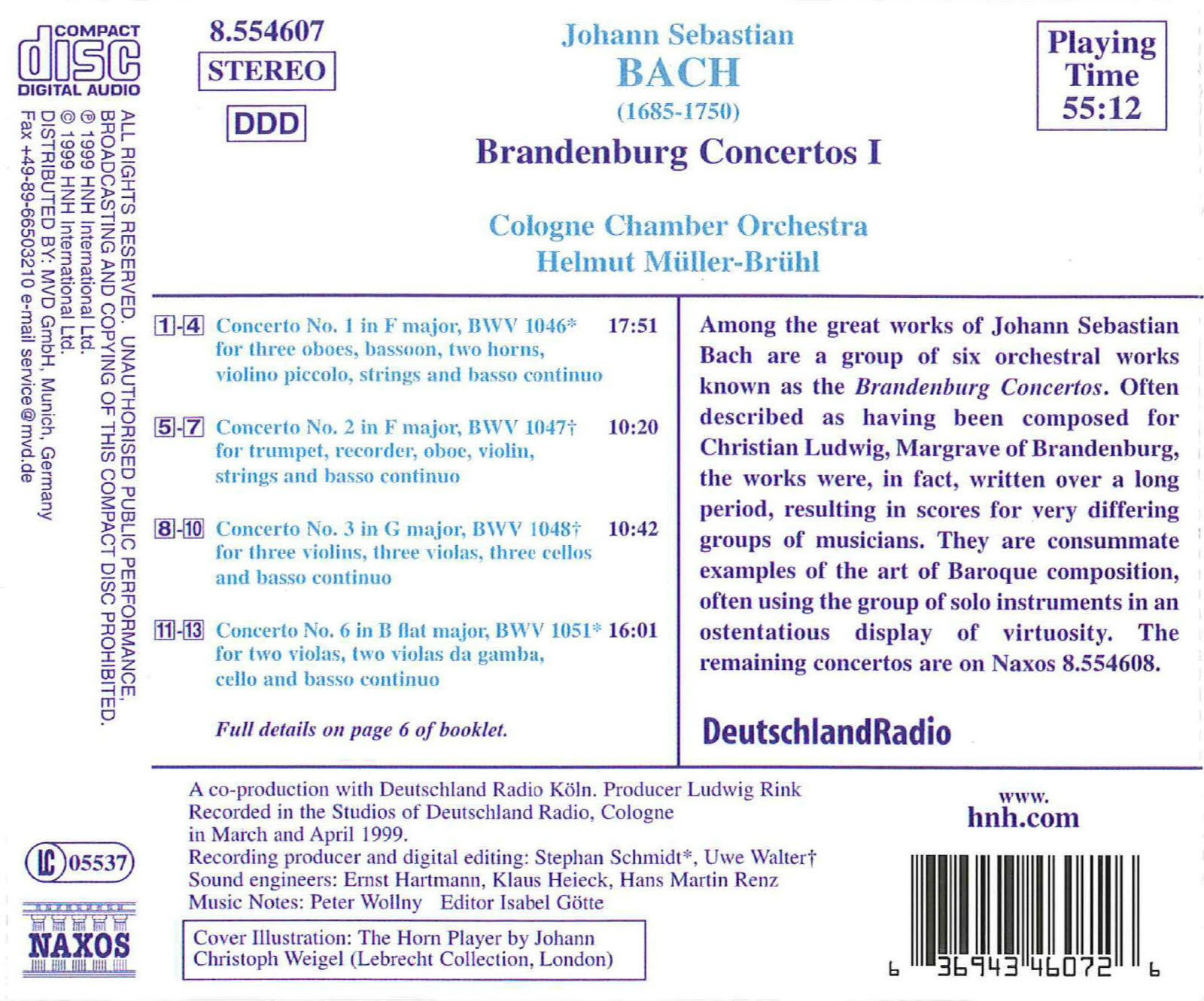

1-4. Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F major, BWV 1046 (17:57)

5-7. Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 (10:26)

11-13. Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 in B flat major, BWV 1051 (16:03)

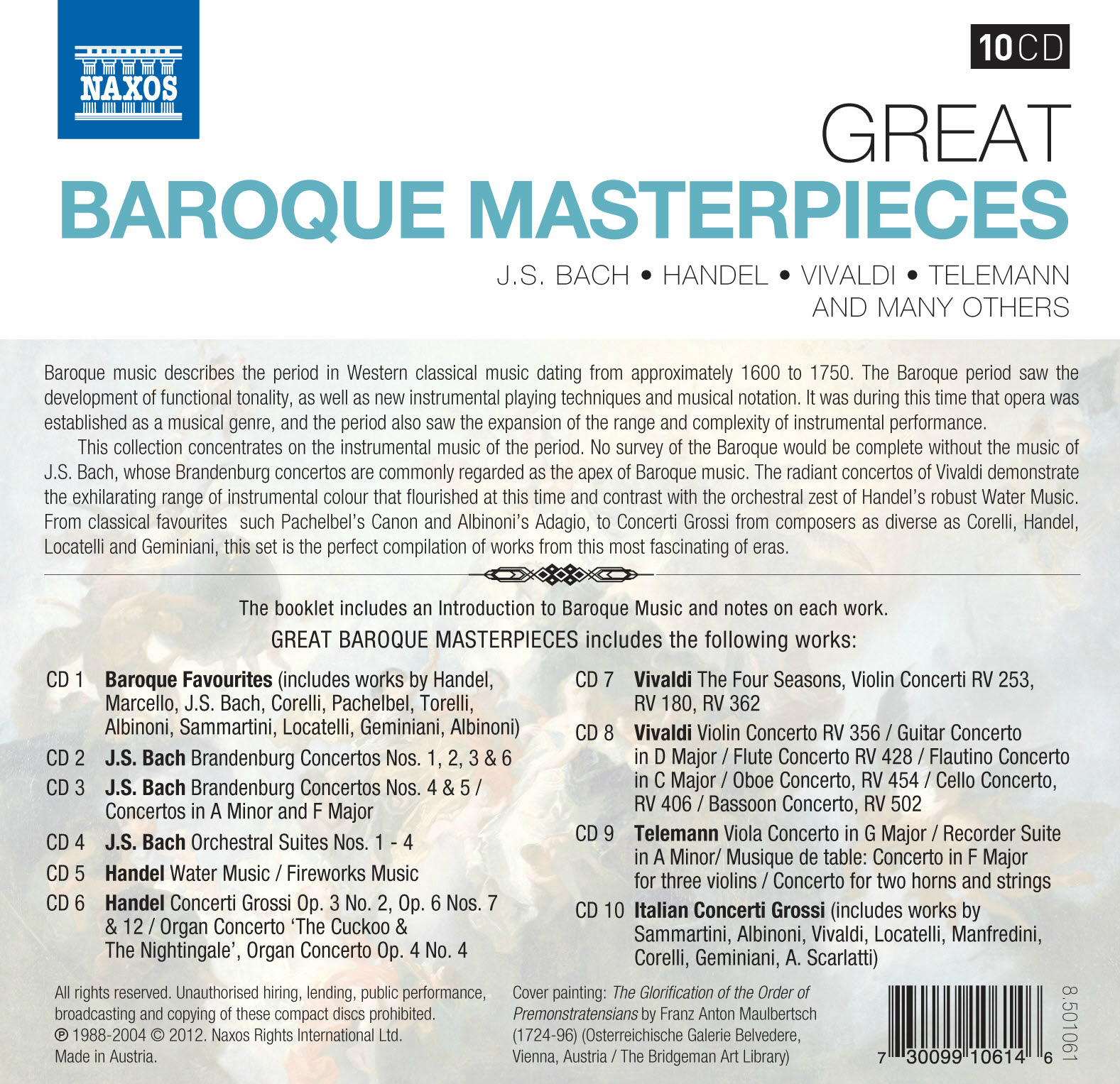

GREAT BAROQUE MASTERPIECES Introduction Various definitions have been proposed for the word baroque, since its first application to music in the eighteenth century. Derived from the Portuguese barroco, a pearl of curiously irregular shape, leading to the French baroque, it was adopted, sometimes pejoratively, as a term descriptive of certain styles in art and architecture, suggesting the exuberance of Bernini and the decorative architectural fashions that followed the Gothic. Whatever its original use, the word, in music, is now generally accepted as the designation of a period from c. 1600 to c. 1750, a period that can conveniently be divided into three of fifty years, Early, Middle and Late. Periodisation, of course, has its dangers and must be used with some discretion. Nevertheless the Early Baroque period, from c. 1600 to c. 1650, covers the age of Claudio Monteverdi and the development in Italy of the art of opera and concurrently of styles of harmony and vocal writing that brought a new strangeness of proportion. The Middle Baroque period, from c. 1650 to c. 1700, is, in England, the age of Henry Purcell, and in Italy the age of the widely influential Arcangelo Corelli, whose instrumental style and forms provided a model for the following generation. The Late or High Baroque, from c. 1700 to c. 1750, is now the most familiar of all. This is the period of Antonio Vivaldi in Venice, of Johann Sebastian Bach in Cöthen and then Leipzig, and of the Italianate German composer George Frideric Handel in London for the greater part of his life. The Late Baroque brought to a height the art of tonal counterpoint, the construction of fugal textures, instrumental or vocal, in which a melody is first proposed by one voice, answered by others in turn, one melodic line set against another. In instrumental music it brings the church sonata and chamber sonata, the first finding room for contrapuntal textures and the second for sets of dance movements, often scored for two melody instruments, with a bass instrument and a chordal instrument, harpsichord, organ or lute, to supply fuller harmonies. Parallel to these trio sonatas of either species is the orchestral concerto, whether in the form of a concerto grosso, in which a smaller group of instruments is contrasted with the full orchestra, or as a solo concerto, a form perfected by Vivaldi. During the baroque period the orchestra developed from a varied collection of instruments to something approaching the form it has today in the string section of a modern orchestra. By the early eighteenth century the orchestra often consisted of first and second violins, violas, cello and bass, with a chordal instrument. This was the form of the orchestra generally used by the violinist Vivaldi. The instrumentation, however, could be varied, as in Johann Sebastian Bach’s vividly orchestrated Brandenburg Concertos, or, to a lesser extent, in George Frideric Handel’s concertos. The solo concerto of the High Baroque brought not only the varied use of solo instruments found among the five hundred or more concertos by Vivaldi, but the appearance of the keyboard concerto, whether in Handel’s Organ Concertos, designed to entertain an audience in the intervals of an oratorio, or in the Harpsichord Concertos Bach wrote or arranged for himself and his sons with his Leipzig University Collegium Musicum. The present collection concentrates on the instrumental music of the period, principally of the High Baroque. The years also brought new forms of opera, from the mixed genres of the Middle Baroque and the old age of Monteverdi to the formal opera seria adopted by Handel and his contemporaries. In England it brought a new form, the English oratorio, largely Handel’s creation, while France had seen the apotheosis of French ballet and opera first with Lully and then with Rameau. CD 1 starts with an instrumental excerpt from a Handel oratorio, The Arrival of the Queen of Sheba from Handel’s Solomon. The last CD ends with a concerto grosso, by Alessandro Scarlatti, whose operatic overtures led the way to the new symphonies of future generations. Every age, we are reminded, is an age of transition. Keith Anderson

CD 2 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) CD 3 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)

Bach - Brandenburg Concertos Johann Sebastian Bach belonged to a dynasty of musicians. In following inevitable family tradition, he excelled his forebears and contemporaries, although he did not always receive in his own lifetime the respect he deserved. He spent his earlier career principally as an organist, latterly at the court of one of the two ruling Grand Dukes of Weimar. In 1717 he moved to Cöthen as Court Kapellmeister to the young Prince Leopold and in 1723 made his final move to Leipzig, where he was employed as Cantor at the Choir School of St Thomas, with responsibility for music in the five principal city churches. In Leipzig he also eventually took charge of the University Collegium musicum and occupied himself with the collection and publication of many of his earlier compositions. Despite widespread neglect for almost a century after his death, Bach is now regarded as one of the greatest of all composers. Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis numbers, abbreviated to BWV, are generally accepted for convenience of reference. On 20 April 1849 Siegfried Wilhelm Dehn, at the time custodian of the music collection in the royal library in Berlin, reported a remarkable discovery. “While compiling my catalogue of the works of Johann Sebastian Bach existing in Berlin I have come across many works of the greatest significance which up till now have remained unknown (unknown even to his sons Carl Philipp Emanuel and Wilhelm Friedemann as well as to Forkel, who is always so exact), among them six concerti grossi dedicated to the Margrave Christian Ludwig of Brandenburg.” Since Philipp Spitta’s monumental Bach biography the name Brandenburg Concertos has established itself for these concertos, which were thus awoken, like the Sleeping Beauty, from over a century of slumber, and under this name they are today among the most well-known works of the composer, in fact of the musical literature of the whole world. In the Brandenburg Concertos Bach enriched the concerto genre in many significant aspects and ran the gamut of possibilities the genre presents. It is not easy to find a comparable cycle of works of this era which manages to combine bold experiment with solid craftsmanship and musical richness with conceptual consistency in such perfection. The first Brandenburg Concerto in F major BWV 1046 contrasts three groups of instruments (horns, oboes, strings) with one another, fusing together in the first movement into a complex texture of motivic layers and in the third movement providing a subtle accompaniment to the virtuoso solo passages of the violino piccolo. The sostenuto second movement uses only the oboe and the string groups, the upper voices of which spin out wide sweeps of filigree melody. The third movement is followed by a colourful series of dance movements divided up by the rondo-style repeats of the minuet. The second Brandenburg Concerto in F major BWV 1047 presents an intricate solo quartet consisting of trumpet, recorder, oboe and violin, to which the tutti strings take second place as far as independence of texture and thematic significance are concerned. The observation that the orchestra merely takes on the function of a basso continuo accompaniment has led to the supposition that the work was originally conceived as a chamber concerto for four soloists. The particular feature of this concerto lies in the way the four instruments, which are so different in sound quality, are given exactly the same melodic treatment. The third Brandenburg Concerto in G major BWV 1048 is scored for three groups, each consisting of three members of the violin family (three violins, three violas and three cellos). Here Bach ingeniously makes use of the various possibilities of combination: in one place the musical texture is shared between high, middle and low registers, in another place between three string trios, and occasionally individual representatives of each group come into prominence as soloists, A formal peculiarity of this work is the fact that the middle movement is missing; the two fast movements, which differ from each other significantly in their mood and texture, are connected with each other merely by means of a short transitional cadence. Brandenburg Concerto No 4 in G major BWV 1049 is scored for a concertino consisting of a violin and two recorders. The consequence of this for Bach was that the violin could be used not only as a virtuoso solo instrument above the accompaniment of the tutti strings, but also as a continuo instrument for the two recorders. Particularly in the first two movements of this concerto the playful changing-around of formal and thematic hierarchies of the concerto form can be detected. In the last movement Bach concentrates his forces in order to achieve a bold compositional tour de force—the seamless amalgamation of fugue and concerto form. The ritornellos of this movement thus become fugal expositions, the solos become episodes with thematic connections. Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D major BWV 1050 may well be the first piano concerto in musical history. The virtuoso soloist is here supported by a small concertino consisting of flute and violin which displays an astonishing autonomy from the motivic-thematic point of view. The imposing harpsichord cadenza which almost bursts the boundaries of the movement was added by Bach while he was preparing the definitive score for the dedicatee—presumably in order to remind the Margrave of his own skill as a virtuoso. After the slow movement, an intensively worked-out quartet setting, the work concludes with a cheerful Gigue, which, like the finale of the fourth concerto, is in fugal form—although in a looser formal structure. Finally, the sixth Concerto in B flat major BWV 1051, scored for the unusual instrumentation of two violas, two viole da gamba and cello obbligato, represents a daring mixture of elements from the era before and after Vivaldi. Whereas the two gambas take over the function of an accompaniment to a great extent and only participate in the thematic process with short interpolations, the two violas fulfil an extraordinarily virtuoso function which far exceeds that which was usually demanded from this instrument at this time.

The Concerto in F major BWV 1057 for harpsichord and two recorders represents Bach’s own transcription of his Brandenburg Concerto No 4. In this transcription, which was written around 1738/39, at the same time as the other harpsichord concertos, Bach left the string passages for the most part unchanged and also retained the two recorders which characterize the sound quality of the original version. In contrast he transcribed the virtuoso part of the solo violin for the harpsichord, and in doing so took particular care to re-write the idiomatic violin figurations to make them suitable for the new instrument. In his transcription Bach retained the finely graded interrelations between the various instruments (not only within the trio of soloists but also between concertino and ripieno), extending the trio sections to a four-part texture by means of a newly composed additional part. The Concerto for flute, violin and harpsichord in A minor BWV 1044, the so-called Triple Concerto, occupies a special position within Bach’s concerto oeuvre. As far as its instrumentation is concerned the Brandenburg Concerto No 5 can be regarded as a companion work, but the history of its composition, its gloomy and elegiac character and its extraordinary intensity make it unique; it can be regarded as Bach’s most unusual contribution to the concerto genre as a whole. By reason of its mature style it is probable that the work was composed in the 1740s. As is the case with the other concertos with harpsichord obbligato, the Triple Concerto is based on works of which some were written quite a long time before; unlike the F major Concerto, however, this is not the transcription of a violin or wind concerto from the Cöthen period, but the radical re-writing of pieces for solo harpsichord or organ. The outer movements of the work are based on a Prelude and Fugue (BWV 894) written not later than 1714, whereas the middle movement is an arrangement of the second movement of the Trio Sonata for organ, BWV 527. Unlike the other concerto transcriptions, in which only the relevant solo parts had to be adapted to the new medium, the material of the prelude and fugue was here adapted for the solo sections of the harpsichord, to which Bach then composed new additional parts for the two other solo instruments as well as all the orchestral parts. He ingeniously extended the original trio structure of the charming middle movement to a quartet which—with an exchange of parts in the repeats—is performed by the soloists alone. With this concerto Bach succeeded in creating a coherent whole, the ingeniousness and remarkable originality of which convincingly refute the various doubts expressed about its authenticity.

|

'클래식' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 라흐마니노프: 슬픔의 삼중주 라단조 2번, Op. 9 - Budapest String Quartet | 音香 클래식 (0) | 2017.11.26 |

|---|---|

| 베토벤의 음악 & 책을 읽어주는 여자 (La Lectrice 1988) - 미셀 드빌, director (0) | 2017.11.25 |

| 바흐: 브란덴부르크 협주곡 제1번 바장조 BWV 1046 - Hans Reinartz, cond (1974 PYE Collector) (0) | 2017.11.18 |

| 앨범: 위대한 바로크 걸작 CD 1, 좋아하는 바로크 - Various Artist (2012 Naxos) (0) | 2017.11.17 |

| 헨델: 오라트리오 Solomon HWV 67 중 '시바 여왕의 도착' │ 고대 바로크 (0) | 2017.11.17 |